Insights

Building Hope: The Rosenwald Schools Initiative

By

It took me 35 years as an architect to find the story that crystallizes what Simon Sinek calls my “why.”

I have always believed in the power of education to change people’s lives for the better. And as an architect focused on the design of K-12 schools, my mantra is, “It’s all about the kids.” But as hard as it is to improve the life of one child at a time, can our schools really affect societal change?

The Rosenwald Schools Initiative proves that the answer is yes.

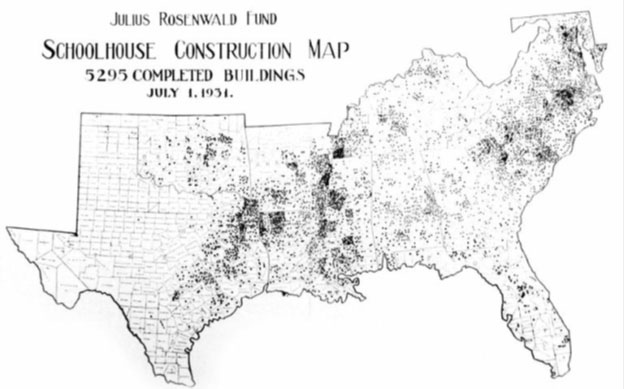

From 1915 to 1932, Julius Rosenwald, the president of Sears Roebuck Company, was the catalyst for the construction of 4,977 schools for African-American students across the United States. No, that is not a typo. 4,977 schools, built in just 17 years.

Change that began with collaboration

The story of the Rosenwald School Initiative is one that speaks to the power of visionary leadership and to the necessity of collaboration.

In the early 20th century, more than half of the United States suffered under the yoke of public school segregation, as states applied the Jim Crow laws of “separate but unequal.” African-American students were forced into dilapidated school buildings that housed up to 80 students to a room. But that began to change when Julius Rosenwald met his future collaborator, Booker T. Washington, head of the Tuskegee Institute.

Washington asked Rosenwald to serve on the board of the Tuskegee Institute in 1912, which Julius did for the remainder of his life. However, their partnership became so much more.

In response to the dismal state of African-American schools, Rosenwald and Washington established the Rosenwald School Initiative to provide rural communities with funding to build quality school facilities for African-American students.

Progressive architecture

As a school architect, two things strike me about the Plan Book schools that are the hallmark of the Rosenwald Initiative.

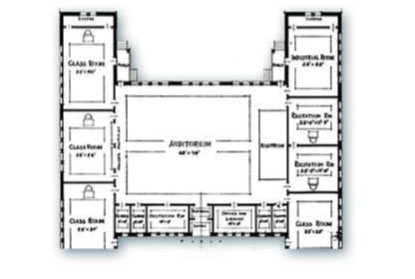

First, these school designs are far ahead of their time. The Plan Book designs, which ranged from one-teacher plans to seven-teacher plans with an auditorium, addressed the issues of natural daylighting, indoor air quality, flexibility and community use that we still discuss today. Many of the schools even included an operable wall, and each of the plans included a North/South and East/West concept to make the best use of light.

Second, the Rosenwald School Initiative was a true community effort. Julius Rosenwald and The Rosenwald Fund provided 25 percent of the required money for construction, but the rest came from the local community. In fact, Rosenwald funds accounted for $4.4 million of the entire $28 million program, with African-American communities raising $4.7 million and state and local governments adding another $18 million.

Over the next 17 years, the Rosenwald Schools Initiative greatly improved the quality of education for African Americans in segregated states. By 1932, Julius Rosenwald and Booker T. Washington (who died in 1915) had created a system of 4,977 new schools, 217 teacher homes and 163 shop buildings. In fact, by the end of 1932 one third of all African-American children in the South attended a Rosenwald School.

Rosenwald Schools and Brown vs. Board of Education

While the Rosenwald Schools Initiative was completed long before Brown vs. Board of Education, I believe that new educational opportunities were one of the factors that disrupted segregation.

Brown vs. Board of Education has its roots in the sermons of Rev. J.A. De Laine, Sr., a South Carolina preacher who preached that each man, woman and child is born into a life of “sacred opportunity.” His advocacy for equal access to education resulted in the lawsuit which eventually became the landmark Supreme Court decision.

By the time Brown vs. Board of Education became law in 1954, Rosenwald Schools had been operating for more than 30 years. An eight-year-old student attending a Rosenwald School in 1930 would be a 32-year-old, well-educated man or woman in 1954. And such a person would be willing and able to fight for that “sacred opportunity” described by Rev. De Laine. The promise of the Rosenwald Schools Initiative was fulfilled in that 1954 Supreme Court decision, and it continues on today.

In 2016, only 10 percent of the original Rosenwald Schools remain standing. My company, Fanning Howey, has been fortunate to be a part of the restoration of two Rosenwald Schools: Panther Branch Rosenwald School in Garner, North Carolina, and Free Hill Rosenwald School in Free Hill, Tennessee. But no matter what the condition of each of the 4,977 Rosenwald buildings, their legacy remains intact.

I have discussed the Rosenwald Schools Initiative at many conferences, but one moment stands out. After one presentation, a little girl, no more than eight years old, raised her hand and asked, “Mr. Hall, who came up with the idea that white and black kids needed to be separate?”

I had no answer for this girl. But in the example of the Rosenwald Schools Initiative, I had a message of hope. Because as a society, our investment in education will always result in an abundance of opportunity. What began as a vision shared by two men – Julius Rosenwald and Booker T. Washington – ended as better education for more than 150,000 students.

And that is why I do what I do every day – to extend opportunity and hope to all people.

When you stop to think about it, that’s not a bad way to spend a career.

Designing School-Based Health Centers

By Dan ObrynbaSchool-based health centers are becoming integral components of public schools, primarily serving the needs of students and staff, with the potential to also serve the broader community. School-Based Health Centers are usually run by separate

Full ArticleEsports Facilities for Student Engagement

By Steven HerrAs competitive esports becomes a viable career path, educators across the country are embracing these gaming trends and expanding esports programming at their schools. Schools that have adopted esports are already seeing the benefits. According

Full ArticleSmart Schools Roundtable: School Safety by Design

By Zachary SprungerThe tragedy at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas, has once again brought the issue of school security into the national conversation. In 2020, Fanning Howey hosted a school security webinar featuring Michael Dorn, Executive

Full Article